- Upgrade

- Posted

1970s Devon home becomes certified passive B&B

If you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to live in a passive house, a B&B in Devon could be just the ticket. The winner of the private housing award at the 2013 UK Passivhaus Awards, this upgraded 1970s home proves that even existing buildings can be made passive.

This bold retrofit project may be in Devon, but the story behind it starts in Wales.

That's where architect Janet Cotterell of CTT Sustainable Architecture met IT professional Adam Dadeby. Both were studying for a masters in advanced environmental and energy studies at the Centre for Alternative Technology, Machynlleth.

Adam's interest in energy policy had attracted him to the masters. But as time went on, the architectural side of the course drew him in.

Concerned about energy security and climate change, he planned to sell his London home and move to the south-west of England to build a low energy, ecological home. The passive house concept hooked him.

"It's very evidence based, and it's pragmatic," he says. "I'm not a very hair-shirt green, I like to be comfortable."

His initial plan was to build new, but the difficulty of finding land and getting planning permission nipped that in the bud. Together with his wife Erica, he bought a run-down cavity-wall house on a modernist estate in Totnes, Devon, and planned to retrofit.

"I can't think of any part of the house that wasn't wrecked," he says. "Except for total structural collapse, everything else you could think of was a mess." Enerphit, the Passive House Institute's less onerous standard for retrofit, didn't exist at the time, so Adam aimed for full passive house certification.

He interviewed other architects, but ended up hiring Janet. The two interviewed a handful of builders and – rather than going to tender – selected Jonathan Williams, whose background is in conservation building, and negotiated a price with him. "Jonathan understood what passive house was all about," Adam says. According to Janet, Jonathan was the only builder they interviewed who had read up on passive house, and understood how hard it would be. “Jonathan's conservation background meant he knew to take care,” Janet says. “And he had a team of trades that he worked with regularly, which helped greatly.”

The first step was to externally insulate the house. Adam wanted to use a natural material, but doing so would have resulted in very thick walls. What's more, the team couldn't heavily insulate the ground floor (though they did put in 80mm of phenolic and 20mm of woodfibre insulation here) without lowering the room height or undertaking expensive groundworks. So in order to hit the passive house standard, they had to compensate by pushing the thermal performance u of the walls even further.

That meant using a high performance, synthetic insulation — 180mm of Kingspan Insulation UK K5 phenolic board — rather than a natural material. The external insulation helps to eliminate thermal bridging too.

The existing wall cavity was filled with polystyrene Instabead, while insulating autoclave aerated concrete blocks were used to rebuild and extend wall sections that were close to collapse. Upstairs, the team extended the building upwards to add a third floor and insulated the new roof with Warmcel cellulose insulation – made from recycled newsprint – plus Thermafleece sheep’s wool in the service cavity.

Janet designed a new 30 square metre timber frame extension that serves as an entrance area. The walls and roof feature Warmcel-insulated Steico I-joists plus sheep’s wool-filled service cavities. There's also a "living roof" planted with local wildflowers.

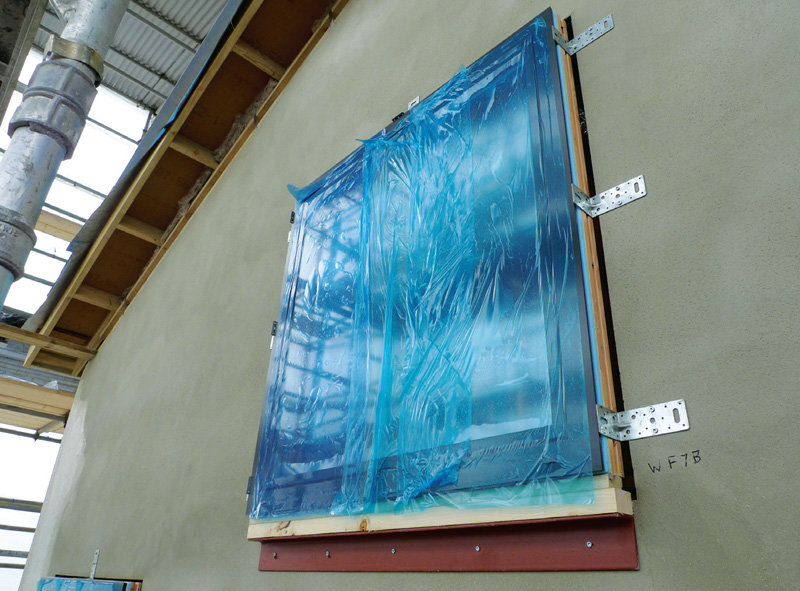

Windows are bracketed onto walls prior to external insulation installation to ensure a continuous insulation layer

Windows are bracketed onto walls prior to external insulation installation to ensure a continuous insulation layer

"I just like the idea of the small section timber I-joist, using low grade timber, and using as little of it as possible, and using the recycled newspaper [insulation]. It just seemed a sensible use of materials to me," Janet says.

The whole house scored 0.40 air changes per hour on its first airtightness test, and a jaw-dropping 0.2 at certification.

According to Janet, this result is down to meticulous detailing and education across the project team. "We didn't end up having an airtightness champion because everyone was the airtightness champion," she says. “Everything was very carefully planned, so that virtually no changes were needed on site.”

The team chose triple-glazed Internorm Varion units and Varion 4 ‘2 + 1’ units, which feature double-glazing plus an integrated blind — to control overheating — that's enclosed by a third pane of glass.

These later units have an average overall U-value of 0.93, which may not be sufficient for passive buildings in colder climates, but are suitable for mild south Devon.

Janet paid close attention to shading design, and says the house stayed cool during this summer's heatwave. "We did the shadings quite well. It's one thing with PHPP you can fudge a bit," she says. Designers must get shading right to prevent overheating, she says, otherwise people will say the passive house concept doesn't work.

"The house is very comfortable and our bills are very low," Adam says. Internal temperatures are steady, and when they change they do so very gradually. The only major overheating problem occurred when over 150 people attended an open day at the house during a spell of warm weather.

But during the cold winter of 2012, the ground floor was actually a little cooler than upstairs — most likely because the floor is only insulated to a U-value of 0.2, and because there's a thermal-bridge at the wall-floor junction.

Janet says there's an important lesson here: that while passive house designers can compensate for less-insulated surfaces by adding more insulation elsewhere, for comfort every opaque surface in the external envelope should ideally hit the recommended maximum U-value of 0.15.

The house's only source of mechanical heating is the heat recovery ventilation system, which u includes a small duct radiator in the supply air that's fuelled by a little gas boiler. Adam’s thinking of adding a radiator downstairs to deliver more heat there, but might take out the duct heater if he does.

"I was quite determined not to have radiators, and I should have been more pragmatic," Adam says. He admits that not installing a full central heating system was akin to taking a leap of faith.

The extension features a living roof

The extension features a living roof

But he's still very comfortable — during his first winter the duct heater had yet to be installed, but he heated the whole house to about 19C with a small oil-fired radiator on its lowest setting (400W).

Solar thermal panels contribute to the house's hot water, and Adam also installed a solar photovoltaic array with a 4kW peak output. He installed PV partly for environmental reasons, but also because the feed-in tariff on offer at the time was quite generous. "Purely in money terms it was worth it," he says.

But the solar thermal and PV panels are facing west and east respectively, a constraint of the planning conditions. "Our wintertime renewables generation is consequently much lower," Adam says.

Perhaps surprisingly, in hindsight he's unsure whether such a deep retrofit is always the right solution for projects like his — in economic or environmental terms.

Building a new house, he reckons, would have cost less (principally because he would have got a big Vat discount for new build). And in carbon terms, he would have been able to use natural, low embodied energy materials throughout the build.

Nonetheless, the project won in the private housing category at this year's UK Passivhaus Awards and the whole Totnes team — Adam, Janet, Jonathan — went on to collaborate on various projects.

The trio have since founded Passivhaus Homes, a design-and-build passive house firm that is developing a 'kit-based' approach to building passive homes to bring costs down. They've just completed their first prototype. The company is also looking at working with community land trusts to develop new, affordable passive homes.

"We feel this is a much better way to deliver low cost housing to the people who need them," Janet says. "It cuts out the commercial profit driven volume house builders and puts the local community back in the driving seat."

The trio have also launched a web business, the Passivhaus Store, which aims to streamline the supply of passive house suitable building materials and systems. Adam and Janet have also written The Passivhaus Handbook, which is published by Green Books/UIT. "The book is a distillation of what we've learned from the project," Adam says.

The bright, sleek yet ecological kitchen

The bright, sleek yet ecological kitchen

Meanwhile, Adam and his wife Erica have opened up their Totnes passive house as a bed and breakfast. Adam says half their guests are people thinking of building their own passive house, visiting to get a taste of what it's like to live in one.

So, if you really want to get a feel for the project, you could always go and check it out for yourself.

Adam blogged extensively about the project at http://passivhausrefurb.blogspot.co.uk

Selected project details

Client: Adam Dadeby & Erica Aslett

Architect: CTT Sustainable Architect

Contractor: Williams & Partners

PHPP: Adam Dadeby

Passive house certification: Warm

Airtightness consulting & testing: Aldas

External insulation (retrofit): Kingspan

Cellulose insulation: Warmcel, installed by Ecofill

Sheep’s wool insulation: Thermafleece

Wood fibre insulation: Steico & Pavatherm

Cavity wall insulation: Instabead

Insulated foundations: Celotex

Airtightness products: Ecological Building Systems

Windows: Internorm

Masonry thermal blocks: Travis Perkins

Thermal breaks: Foamglas

Plaster: British Gypsum

MVHR: Paul

Solar thermal & modulating boiler:

Rotex, supplied by Responsible Energy Management

PV array: Mobasolar

PV inverter: Fronius

Additional info

Project overview:

Building type: 162 square metres retrofitted & extended cavity-wall detached house including 30 square metre timber frame extension.

Location: Totnes, Devon

Cost: £330,000 construction plus £44,000 for architectural and other professional fees

Passive house certification: full certification achieved

Space heating demand (PHPP): 13kWh/m2/yr

Heat load (PHPP): 9.3W/m2

Cooling load (PHPP): 4W/m2

Primary energy demand (PHPP): 68kWh/m2

Primary energy demand (measured): 76kWh/m2

Airtightness: 0.2 ACH

Upgraded walls: 180mm rendered Kingspan K5 phenolic external insulation on 100mm original block, followed inside by 50mm cavity insulated with Instabead Graphite K32, then another 100mm block. U-value: 0.095

Upgraded ground floor: 14.5mm Kährs hardwood floor finish on 2mm foam underlay, followed underneath by 20mm Steico woodfibre insulation, 80mm Kingspan K3 insulation, 10mm plaster and original 150mm slab. U-value: 0.2. Glapor foamed glass gravel insulating aggregate outside three perimeter walls.

New roof on existing dwelling: 24mm woodfibre board externally, followed below by I-joists with 350mm Warmcel cellulose insulation, 50mm service cavity insulated with sheep’s wool, plasterboard. U-value: 0.104

Extension walls: 24mm woodfibre board externally, followed inside by vertical I-joists insulated with 400mm Warmcel cellulose insulation, 50mm sheep’s wool-insulated service cavity, and plaster board internally. U-value 0.093

Extension floor: Kährs hardwood floor as above, on 20mm Steico woodfibre insulation, 50mm sheep’s wool batts, 150mm slab, and 200mm Xtratherm PIR insulation. Two courses of Foamglas Perinsul blocks at perimeters under toe of slab. U-value: 0.075

Extension roof: OSB board externally, followed below by I-joists with 350mm Warmcel cellulose insulation, 75mm sheep’s wool insulated cavity, and 12mm plasterboard. U-value: 0.107

Windows: Internorm Varion triple-glazed windows/ Varion 4 ‘2 + 1’ glazing. The Varion 4 units have integrated blinds for summertime shading. Spacer-psi value 0.05W/mK, g-value 0.6 on solar gain facades, double e-coated, Argon filled. Overall U-values: 0.75-0.93

Heating: post heater in MVHR supply air fuelled by 20kW Rotex gas boiler (modulates down to 4kW). Plus 9.4m2 of west-facing Rotex roof-integrated solar thermal drainback panels with Rotex 500 litre thermal store.

Microgeneration: 3.99kWp Mobasolar photovoltaic array with Fronius IG TL transformerless inverter

Ventilation: MVHR Paul Novus 300, 0.24Wh/m3, 93% HR efficiency