- Case Studies

- Posted

Back to the Future

With the explosion of interest in sustainability over the last few years it would be easy to think that Ireland has no history of environmentally conscious building. While true to a large extent, such a view ignores some early attempts to change construction approaches in Ireland. Jason Walsh visited the Green Building, a pioneering sustainable development built in Dublin's Temple Bar in 1994, to find out how one of Ireland’s most ground breaking eco designs has been performing over the last decade.

The Green Building, a mixed-use development in Dublin's Temple Bar district, is emblematic of the pioneering spirit. Designed by engineer Tim Cooper with Murray O'Laoire Architects, it is an innovative mixed use development of offices, apartments and shop units laid out around a six storey central courtyard designed as a semi-external atrium space with a glazed openable roof. The atrium's roof is oriented southwards and designed to naturally ventilate and light the building. The building consists of shops at ground levels with offices at first floor level and eight apartments on the upper three levels. Completed in 1994 it went on to win the RIAI regional award for Dublin in 1995 as well as receiving a commendation for excellence in construction and an overall commendation.

The Green Building makes use of a number of renewable energy sources including photovoltaic solar arrays for electricity, evacuated tube solar panels for hot water, a geothermal heat pump and wind turbines – though the latter have since been switched off.

Additionally, the design of the building and its fabric has been done in such a way as to reduce energy use.

Tim Cooper explains his inspiration for the building was actually not a modern building at all: "It's based on the Museum Building in TCD, a 150 year old building," he says.

Cooper came to know the Museum Building while working at the college: "I had worked in energy management at Trinity College Dublin since 1976, during the oil crisis.

"I've long been interested in energy and energy conservation [and] I tried to establish where the energy was going and created an energy audit. I discovered what was the most energy efficient building in the college – the Museum Building," he says.

According to Cooper, the Museum Building is an example of a structure built with amazing foresight: "If you look at it, it's got chimneys – except they're not chimneys, they're ventilation. The ornamental stone contains holes – the building actually has heat-recovery ventilation, something which many people are only beginning to get around to thinking about now," he says, clearly enthused by the designer's work.

Planning to develop the ideas he gleaned from the Museum Building, Cooper set about devising a strategy for a new energy efficient building. Though not quite stonewalled, Cooper found that his ideas were considered fanciful.

The atrium provides natural ventilation and lighting for the building

Nevertheless, he persevered and eventually received funding to test his ideas by building what was to become the Green Building: "I applied to Europe to get funding and they gave us, in today's money €3 million," he says.

Good news for Cooper but the European funding did come with some strings attached. Ironically, these conditions have actually helped the building and play to its strengths: "It had to be city centre and it had to be a mixed-use development," he says.

On receipt of the funding Cooper ploughed on, working with Murray O'Laoire Architects to design what he considered to be a kind of 'building of the future': "I took all of the best features of the Museum Building and built them into this building – it has a big atrium in the centre and has external insulation," he says. "The atrium opens and closes which changes the whole characteristics of the building."

As a result of the seasonal change in the building's profile, the Green Building adapts to the weather conditions, cooling in summer and retaining heat during the winter months.

"I also kept window to wall ratios low," says Cooper, "and designed a very high radiant surface area so that you can heat the building using very low temperature hot water."

Urban life

Miriam Barror, a financial executive with Forbairt Naíonraí Teoranta, a voluntary organisation that supports the promotion of education and children's care services in Irish, lives in a two bedroom apartment in the Green Building.

"It's a gorgeous apartment," she says. "The atrium is beautiful – the roof opens to let in cool air – the electricity is cheaper [and] the two bedroom apartments have bay windows that move around to create a balcony" she says. "I don't pay for heating at all."

She is also keen to stress that life in the Temple Bar district has other sustainability benefits: "In terms of living in the city centre, you can walk everywhere you need to get to."

Miriam's experience of the building has been overwhelmingly positive, noting that it does not feel like a typical Dublin apartment in many ways: "This is a really solid building," she says, "it's a really solid structure with high ceilings."

Despite the apartment's relatively compact size, good ergonomic design has resulted in a suitable space for living: "The kitchen is quite well designed – everything has a space," she says, the only real criticism being that "a bigger hot press would be nice."

Noise is also a factor with apartment living. After all, it isn't unusual to have four neighbours – two at the sides and one above and one below – or more. According to Miriam, the Green Building does not suffer from serious noise problems: "It has been designed to keep noise-flow to a minimum. Once you shut the door, you're sorted."

Having lived in the building for some time, Miriam has recently bought her apartment – a sure sign that the experience of living in the building is a positive one: "I can't wait for summer, I'm expecting very low electricity bills," she says.

The building's facade

Natural energy

Although the Green Building makes use of an extensive range of recycled materials and rainwater harvesting along with exterior insulation and other environmentally sound technologies such as double and triple glazing (and, at one time, using an energy saving control system that automatically received weather data directly from Met Éireann, using it to predict heating requirements for the following 48 hours) its main claim to sustainability lies in its energy production strategy.

Though hardly a hermetically sealed unit, the building does produce its own heat, hot water and electricity on-site through a range of renewable energy technologies. At the design stage, the decision was taken to utilise every available energy source, resulting in the use of solar panels, both photovoltaic and evacuated tube, wind turbines and a ground source heat pump.

While the solar panels and heat pump have both proved a success, the wind turbines have not. Tethered for several years, they are set to be decommissioned soon. The problems have been two-fold: firstly, their vibrations were heard in the penthouse apartments causing some discomfort for residents and, secondly, they failed to reliably produce power due to turbulence.

On the other hand, the solar sources are rather more useful. The annual output of the grid-connected system was initially estimated at 2,731 kWh, and currently runs at around 3,000 kWh.

The building exports surplus power to the national grid: "The electricity is given to the nation free," laughs Cooper, "five percent is for export," noting that currently electricity cannot be sold directly to ESB.

Nevertheless, as a measure of the building's success, regardless of any absconded potential profit as a result of the regulatory environment for electricity in Ireland, the value of the electricity the building produces now exceeds the cost of all the electricity required for the heating systems.

Additionally, the photovoltaic arrays have required no maintenance during their first twelve years other than the replacement of three fuses after a violent thunderstorm.

In the initial design, the roof-mounted wind turbines and photovoltaic panels charged a bank of heavy duty batteries. Batteries have a limited lifespan of around ten years, by which time it was anticipated that legislation would be in place to switch to grid-connected inverters.

High-efficiency evacuated tube solar collectors feed into the building's hot water supply, combined with a bore hole heat pump

"When we first put them in we couldn't grid connect," says Cooper, "so we had to put in the massive accumulator and a stack of inverters. That is now all redundant."

Clearly this is a significant development not only for Cooper and the Green Building, but for sustainable energy use in general: "The grid-connected photovoltaic alone is much more efficient than the photovoltaic and turbines were together, before."

The reason for this is straightforward: the grid-connected inverters have the advantage of allowing the solar photovoltaic electricity generators to operate continuously at maximum capacity. During periods when output exceeds demand, surplus power is exported to the grid. "The whole operation is a fully-licensed electricity generation plant," says Cooper.

Electricity meters show the energy generated by the photovoltaic panels, expressed (above) in kWh, and (below) in watts

In fact, the solar has been so successful that Cooper's latest venture is Cool Power, a company specialising in the production of electricity from photovoltaic solar panels.

"We initially set up a business for the Green Building. Having got that in place, the system of incentives encouraged us to set up Cool Power, which is a separate entity from the Green Building's management company."

The company works with home and business owners to make solar-generated electricity a reality, importing and locally manufacturing its own photovoltaic arrays and control systems. The company's most novel idea is to supply PV systems to existing and new-build offices, free of charge. The electricity generated by these systems is then sold to the building's occupant. Combined with other building-integrated and retrofitted solar systems, not to mention Cool Power's ability to build solar power stations – the solar equivalent of a wind farm – the company seems to have found an exciting way around the difficulties of selling electricity back into the grid in Ireland.

The Green Building's heat pump, meanwhile, uses a bore hole for its groundwater source, a design feature that is appropriate considering the building's urban location and small footprint.

"I put in a very deep bore hole," says Cooper. "I get a very high coefficient performance, the ratio between the amount of electricity that goes into the heat pump and the heat that comes out. It operates at 4.5 to the low fives," he says. "At five, the 'one' of electricity is primary grid electricity, the additional four is renewable."

The photovoltaic panels produce 3,000 kWh per annum while the heat pump consumes 4,000 kWh per annum, so 75 per cent of the power from the heat pump comes from the solar source. Obviously, the heat pump does not operate twenty-four hours a day (in fact, it comes into action on at around 11PM) and therefore any surplus of solar-generated electricity during the daylight hours is fed into the national grid. "Our net heating bill is minus €300 per annum, and decreasing," says Cooper.

"We saw this project as being a role model for planners, developers and builders. Unfortunately it transpired that we were too far ahead of the posse at that time. Things have changed dramatically in the last year. There is now a huge interest in what we have done in the Green Building," says Cooper.

Running hot and cold

The heat pump was supplied by Coolair. The company's Eddie Lynch explains: "All my dealings were hands on with regard to the original installation and the very limited servicing over the year.

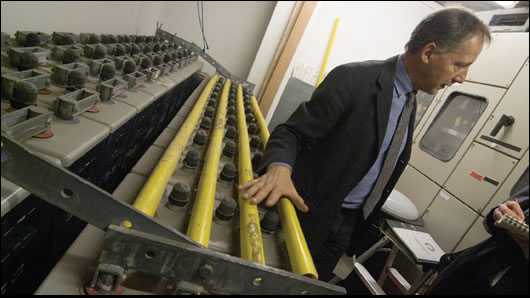

The designer of the Green Building, Tim Cooper, with a bank of heavy duty batteries (above) which have been redundant since the recent grid connect. The batteries had been charged by the roof-mounted wind turbines and photovoltaic panels

"I think it's been a success, most definitely. My view at the time was that it was a good idea. In the early 1990s it [a green building] was one of those conceptual things.

"It all started for us with Tim Cooper. Trinity College, via Tim Cooper, looked at the idea of installing groundwater heat pumps in a lot of the old, stone buildings," he says.

When the Trinity College project went ahead it ran into some difficulties: "They were very successful when they worked but they suffered from [having] an unreliable [water] source," says Lynch.

As a result, how and what the heat pumps should do was re-evaluated: "The heat pumps were activated at night to maintain the fabric temperature in the buildings, stopping the boiler from having to heat up from low temperatures every morning, and that was very successful."

After this experience, Cooper sought to develop the ideas and, with the Green Building, found a perfect opportunity to do so – and a reliable groundwater source.

"It [the idea] was so simple – drill a hole, draw the water up, chill it and extract the heat," says Lynch.

Lynch feels that when the building was in the design and construction phases many people thought of it as a curiosity and were probably quite sceptical about its chances for success, particularly that of the heat pump: "The groundwater source has been key to it and it gives great reliability. If it hadn't worked I don't think a lot of people would have passed comment."

Temperature data from the building indicates during mid-February 2007 that while outside temperatures fluctuated between one and fourteen degrees Celsius, internal temperatures were maintained at base levels of eighteen degrees in the apartments' bedrooms and 21 degrees in the living rooms – incidentally, the same temperatures regarded as appropriate by the UK's West Midlands Public Health Observatory.

Tim Cooper, Evelyn Carey of CareyGlass and Xavier Dubuisson, who recently formed Coolpower to offer photovoltaic electricity solutions for businesses and homes

The ground-source heat pump which utilises bore holes to draw up a substantial amount of free heat on a tight urban site

None of which is to say that the heat pump has not faced difficulties over the years, just that they have been overcome: "There was a problem with the water quality," he says. "Coming from so far down it was corrosive. The original heat exchanger corroded and we sourced and replaced it with a stainless steel one."

Nevertheless, according to Lynch lessons are being learnt from the building's success: "The technology is not yet mainstream in the domestic setting but people are aware of it," he says.

"People look at it and see the capital investment. Many people would like to have a heat pump but they're afraid of the capital cost. You have to think of the payback – in monetary terms, but also in terms of the environmental payback," he says.

Lynch is clearly keen to see further use of renewable energy more broadly in Ireland: "It needs to be introduced almost as legislation – that you can't build hundreds of homes without [using] renewables," he says.

Despite this, he doesn't want to push heat pumps in all scenarios: "With regard to heat pumps, it all depends on the ground source – if you don't have constant water it's no good," he says.

Still, the Green Building does have a constant source of water and the heat pump is performing well and in that regard, despite now being thirteen years old, the Green Building does provide a model for future construction in Ireland: "We meet Tim every Christmas to give it the once-over," he says. "People, up to now, have been so slow to implement the technology [but] if you can do it on the scale of the Green Building, you can do it on any scale.

"At one point Tim was regarded as a bit of a sandal-wearing hippy, a save-the-world guy, but he's smiling now."

Controls for the ventilation and heating systems

- Articles

- Case Studies

- Back to the Future

- green building

- temple bar

- photovoltaic

- solar

- arrays

- evacuated tube

- wind turbines

- geothermal heat pumps

- bore hole

- Coolpower

Related items

-

It's a lovely house to live in now

It's a lovely house to live in now -

Woodland wonder

Woodland wonder -

19 major cities commit to zero carbon buildings

19 major cities commit to zero carbon buildings -

The House of Tomorrow, 1933

The House of Tomorrow, 1933 -

The stunning low energy seaside home that's built from clay

The stunning low energy seaside home that's built from clay -

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather

Mayo passive house makes you forget the weather -

Life in an air-heated passive house - Five years on

Life in an air-heated passive house - Five years on -

Affordable homes scheme reflects rise of Norwich as a passive hub

Affordable homes scheme reflects rise of Norwich as a passive hub -

Larch-clad passive house inspired by a venn diagram.

Larch-clad passive house inspired by a venn diagram. -

Solecco Solar launches new solar roof tiles

Solecco Solar launches new solar roof tiles -

389 sqm home, €200 measured annual heating

389 sqm home, €200 measured annual heating -

A green builder's dream green home

A green builder's dream green home